The product owner is possibly the most misunderstood, or at least the the least understood, role in agile software projects. Just about everyone you talk to, whether a current practitioner of the role or just someone who works in agile projects, will give you a slightly (or greatly) different description of the role, its scope and its value.

A colleague recently asked me to write down for him a brief description of everything I thought a Product Owner should be, in terms of role and responsibility as well as personality and competencies. As I started considering what this would be, a few things occurred to me:

- The list of responsibilities is very broad. The better product owners understand all aspects of a product from the value proposition and business model to design to development.

- The predominant literature on agile product management focusses heavily on the agile process and toolkit: working with scrum or other agile methodologies, continuous delivery, refinement of user stories, etc.

- The traditional (non-agile) literature on product management as a profession is plentiful, but fails to address how the broad scope of product management skills and competencies relate to an agile environment.

I’ve now set out to produce a series of posts which will form my personal description of “the complete product owner”. I’ve chosen the word “owner” intentionally to relate specifically to the field of agile product management (as opposed to, let’s say, “traditional, waterfall” methodologies. More on product owners vs managers soon.) The word “complete” refers to the intention to provide a complete, end-to-end view of the scope and responsibilities of this role.

It is also important to mention at this point that what follows will be most relevant to the traditional home of agile methodologies: in software development. It is interesting to observe how agile techniques are being adopted by industries as diverse as medical research or construction, however the experiences, analogies and resources in this series will be exclusively focussed towards software product management.

What’s in a name? Product Owner versus Product Manager

The traditional industry title for those in the business of managing the product development life-cycle is the “Product Manager”. Agile methodologies, specifically Scrum, introduced the term “Product Owner” to refer to the member of the scrum team (ie, the product team) who is predominantly responsible for the product itself (predominantly, as in agile teams we strive to embed a feeling of product responsibility in everyone, throughout all levels of the product organisation).

Some people misinterpret the difference as a reflection of the scope of the role, assuming that the “Product Management” discipline is broader or more “senior” than an owner. I take a very different view, and argue that there is no difference. It could be perhaps said that within the Product Management discipline, a Product Owner is one who practices within an agile context; however there is certainly not, in my view, an assumption that the scope and responsibilities of a Product Owner are necessarily any different to that of a Product Manager.

In my writings I use the two terms interchangeably; however it is useful to remember that in certain circles the title “Product Manager” is often understood differently from an “Owner”. Specifically in non-software product industries (fast-moving consumer goods, among others) the term “owner” is less relevant.

What is a Product Manager/Owner?

In his famous 1955 work “Designing for People”, Henry Dreyfuss, considered my many as the father of modern industrial design, said the following about the role of the industrial designer:

“The successful performer in this new field is a man of many hats. He does more than merely design things. He is a businessman as well as a person who makes drawings and models. He is a keen observer of public taste and he has painstakingly cultivated his own taste. He has an understanding of merchandising, how things are made, packed, distributed, and displayed. He accepts the responsibility of his position as liaison linking management, engineering, and the consumer and co-operates with all three.”

Although he was talking specifically about the industrial design discipline, I think he has equally perfectly described the role of the modern product manager. (You’ll forgive his gender bias, but it was the 50’s after all). The complete product manager is a jack of all trades. It’s someone who can keep the big picture in mind while obsessing over the smallest details. It’s someone who can, on the same day, discuss or consider engineering process, marketing strategy or interface design – all in terms of how it relates to the core consumer value proposition.

A complete product owner:

- is a technologist,

- is a marketer,

- is a strategist,

- is an entrepreneur,

- is a risk-taker,

- is a visionary,

- is a leader,

- is passionate,

- is a networker,

- is a communicator,

- is a presenter and speaker,

- is a thought-leader,

- is a product expert,

- is a salesperson,

- is fluent in software experience, language and technology,

- understands user experience/user interaction paradigms, and

- understands software development methodology and software development tools and processes.

Where do product owners come from?

The next time you meet a product manager, as an experiment, as them how they became a product manager. If you are a product manager, think about how you became one. If they attended university, ask them what they studied. The answers may surprise you.

Nobody will tell you that they studied “Product Management” at university. Some will have studied Computer Science, others design, still others psychology, business or even philosophy. Nearly nobody will tell you that they “always wanted to be a product manager”. Many of the product owners that I know say they kind of “fell into” the role. I sort of did, too.

Steven Haines calls it the “accidental profession”. The interesting mix of backgrounds and motivations does result in a healthy range of experience and perspectives in the product management world, but it has, I think, the side-effect of producing a problematic diversity in product management approaches and levels of training.

What’s next?

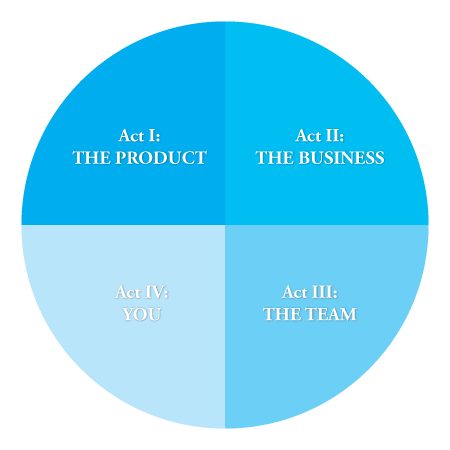

The Complete Product Owner series is broken into four acts. Each act is centered around a main theme: The Product, the Business, the Team, and you.

Some topics don’t fit neatly into a single act. In fact, most don’t. You can’t discuss product strategy without discussing design; you can’t think about market segmentation without thinking about the competitive landscape; and so on.

Within this series, I won’t be able to teach you everything you need to know. I can’t teach you how to do brand marketing or search engine optimisation, for example. The purpose of this series is to discuss the scope of areas, skills and knowledge a Product Owner should understand, what they are and why they’re important; and then potentially provide some links to resources for those who want to know more.

Act I: The Product

Much of the books or literature on product management tends to start with the process and definitions, and leave the actual product to the end, almost as an afterthought. To me, everything starts and ends with the product itself – so we start with the product here. We’ll look at defining what the product is, what it does and who it’s for.

Act II: The Business

The next aspect is the one that I see most often neglected by new and experienced product managers alike. The business is, if not the core element of a product team, the surrounding ecosystem that enables and supports the product development. Smaller teams and startups are intimately familiar with the importance of such business tasks as raising capital funding or developing a competitive business model, but these can go unseen or be neglected in larger teams.

Act III: The Team

This is where most product owners, particularly those new to the profession, spend a disproportionate part their time. The team is where things get done, or “where the rubber hits the road”. Having a functional, efficient and self-organising team is a critical focus for teams. For Product Owners, it’s critical to understand how the team supports you and how you support the team to ensure the greatest success.

Act IV: You – the Product Owner

Once you know what you need to do: the tasks, the responsibilities, the focus areas; how you actually do it is up to you. We’ll look at a number of key skills and competencies that you should focus on developing to be a complete product owner.

Here we go…

So let’s get started. In the first post in the series, we’ll look at defining the product: what it is, who it’s for, and why the heck you’re building it anyway.

I would love for this to be as interactive as possible. If you have questions or comments; if you agree or disagree with what we discuss here, please let me know in the comments.

Resources