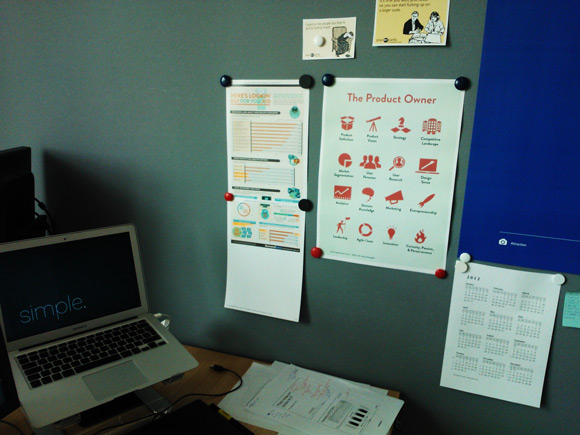

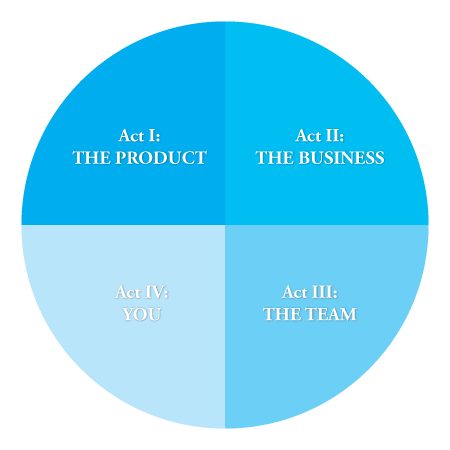

The Complete Product Owner

Act I: The Product

This post is part of the “Complete Product Owner” series.

The centre-piece for any product team – the guiding north star – is the product vision. Where are we going? Why? What do we do when we get there? How will we know when we get there? These are all aspects of a compelling, motivating product vision.

A product vision is more than just a consumer value proposition, and it’s certainly more than a roadmap. It’s an idea, a mission. A pilgramage.

A product vision brings together the product proposition, the core values and beliefs as well as the mission and goals of the company. It answers the question “what”, “when” and, most importantly, “why“.

The Sony TR-55 Transistor Radio

In their great book on developing and communicating vision, Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath describe a great example of a clear, motivating product vision. In post-war Japan many companies were struggling to return to profitability. One small electronics manufacturer, Sony, set out to do something different: they would be the first company to produce a radio that fits into your hand. (Remember, this was a time when radios were pieces of furniture, and electronics manufacturers employed cabinet-makers to construct the elaborate wooden housings in which the electronics were assembled).

The vision was audacious and heavily motivating for employees, and it was clear. It was something everyone could understand and get behind, from the CEO to the factory assembly workers.

If the vision isn’t understood by everyone, it ain’t a vision.

The product owner as a visionary

The best product owners are visionaries. They have a clear idea where their product is going and how it will get there. They can see into the future and understand how various trends, innovations and technologies will come together to create the environment in which the product will succeed.

In his biography of the first years (and 500 million users) of Facebook, “The Facebook Effect“, author David Kirkpatrick reveals how Mark Zuckerberg carries a small notebook with him everywhere he goes in which he writes, in impeccable, tiny script, his thoughts and dreams about Facebook and building the social web. Mark had first imagined the ‘Timeline’ feature as far back as 2007 – a time when his users were still coming to terms with the idea of a news feed – and describes plans to turn facebook into the “social operating system” for the web. Zuckerberg not only understands his product today, he understands where he wants it to go.

Where do you want your product to go? What is the future for you?

The future can be years away. It might never happen. That’s not the point. The point is to understand in which direction the road goes: to have one north star which you share with everyone in your team, so everyone works towards the same goal and in the same direction.

Communicating the vision

What do a product vision, common display advertising and that monster under your bed when you were eight have in common?

Answer: If you stop paying attention to them, they lose their powers.

A vision is only half as useful if it is only stuck inside your head and not being discussed and used by the team on a daily basis. A vision is the most powerful when you share it with the team, discuss it, debate it; let it evolve. You want your team to have a shared understanding about the future as you do. For that, you need to share and communicate your vision.

The vision you have in your head might seem clear enough to you, but if you want to communicate it effectively to a wider audience, you will probably need to spend some time breaking it down into something more clear and succinct. Try writing your vision on paper in one or two sentences.

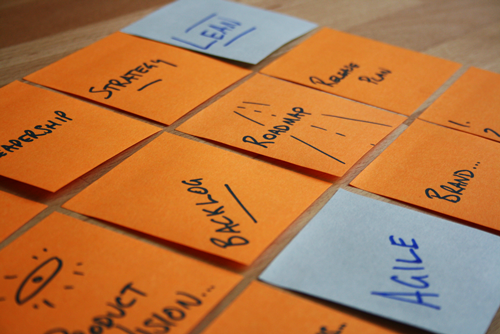

Here are some other techniques to help you refine your vision in written form:

The one-line mission statement

Mission statements got kind of a bad rap in the 90’s, but there is still value in boiling your vision down to one line so simple that everyone can understand it. Like Google’s mission to “organise the world’s information”. The goal is simple enough to understand, but it has majesty and scope (the whole world), ambition, and purpose.

Or the previous example from Sony “to build the first radio that will fit into your hand”.

The Story

Often, a great vision is best communicated with a story.

Take the example of Tom’s shoes from the previous post. Toms’ vision is to bring shoes to needy children in third-world countries. Tom’s communicates the vision with a story of how their founder, Blake Mycoskie, befriended some children in Argentina while he was traveling there, and found they had no shoes. He decided then and there to start Tom’s shoes company to raise money to send shoes to needy children. He returned to Argentina later that year with 10,000 pairs of shoes that he had produced with proceeds from his Tom’s shoes label.

The story not only describes the facts of what happened (he started a company and gave away 10,000 pairs of shoes), but it describes clearly the why. It describes the mission of the company and the core values of generosity and giving, in addition to the mechanics of how the proposition operates.

A fantastic resource on communicating with stories is the book The Story Factor.

The Manifesto

A useful tool for communicating a vision is often the manifesto. A manifesto can be 1 page long or 50. The important thing is that it describes clearly your position, your beliefs, and where you want to go.

Videos or slideshows

If you have some budget or time available you can put together a short video that describes your vision.

A nice example is this video from The North Face showing their brand manifesto.

Regardless what form you use to communicate the vision, remember that the core objective is to communicate a message that us clear, understandable and that will stick. For more tips on communicating a vision that sticks, I can strongly recommend Made to Stick.

A shared vision

Every product team can tell you how important it is that the product owner is available and accessible to the team. That’s true… but no product owner can be everywhere 100% of the time, and there will always be situations where decisions need to be made without you. The best teams work effectively and efficiently when you’re not around. In fact, the more good decisions the team can make without you, the more independent, engaged and effective they will be.

If the vision that you communicate to your team is short-term and focused purely on immediate deliverables, then the team cannot see ahead to know what’s coming next. It’s impossible to know what’s important if you don’t know where you’re going. Teams in this situation will always find themselves relying on the product owner to make all the product decisions.

On the other hand, teams who share your common vision of the future and the product have the same context as you to make product decisions. They understand where the journey is going, and as a result can more easily figure out how to get there for themselves.

It’s unrealistic to think that you can make every product decision yourself, and product owners who try usually fail; especially in medium to large-sized product teams. But when the team can make decisions for you, not only does it lead to more empowered and motivated teams, it frees up your time and attention to focus on more important things. Effectively communicating the product vision is the key to ensuring the team has the same idea as you about where you need to collectively go.

Live the vision

The last thing to remember about the product vision is that you, as the product owner, need to live the vision through more than just words. Make the vision a part of everything you do. This doesn’t mean just putting a poster up in the hall with your mission statement: it means making the vision the core of what you do.

During the development phase of the first Palm Pilot handheld organisers, co-inventor Jeff Hawkins went around for months with a block of wood in his pocket shaped roughly like what became the first palm device. At every appropriate point in a meeting or a conversation, he would pull it out and pretend to enter or retrieve some information from it, to test what it would be like to use one in real life. This not only helped him understand his product at a much deeper level, but it helped his team, observers and onlookers understand what they were there to achieve.

Keep your vision close to your heart, and live it with every decision and discussion.

Summary

The product vision is your north star. It guides you and your team towards your collective destiny. The product owner is responsible for defining and communicating the vision to the product team, and remember: if it’s not understood by everyone, it ain’t a vision.

In the next post in the Complete Product Owner series, we’ll look at setting product goals.

Resources