Last week Facebook announced the new Paper app – an app that turns your Facebook news feed into your own personal newspaper. At the same time they announced Facebook Creative Labs and promised further small, single-purpose apps.

This is all part of a growing trend from Facebook to un-bundle their core mobile product/service into smaller, focussed single-purpose apps that solve specific problems. The first move here was Facebook Messenger, which was designed to compete head-on with the growing number of successful messaging apps that are growing incredibly in the marketplace (Whatsapp, Line, WeChat, Snapchat, etc).

When the giants of the desktop web era (Facebook, LinkedIn, Yahoo, and so on) moved to mobile, to begin with their service architectures stayed more or less intact. On the web, a single product has a single URL, a single brand and a single interface and structure. Facebook on the web is an entire product service that exists behind the facebook.com URL.

It turns out on mobile, however, that there are different dynamics driving user behaviour and expectations. On mobile, how users interact with apps, and how they choose to create and consume content, is very different than it was on desktop.

The structure of apps and the multi-tasking abilities of modern smartphones makes changing apps really easy. It is nearly always easier and quicker to press the ‘home’ button on your smartphone and open another app than it is to navigate the menu structure within the app you’re already in to access a different function.

This dynamic is driving the un-bundling of Facebook’s offer. Others are following. Yahoo already has offered a variety of mobile products since Marissa Mayer joined as CEO. Others, such as LinkedIn, will surely follow. (LinkedIn experimented with an email application, which they have since pulled. I predict they will release a news reader, similar to Paper, some time soon).

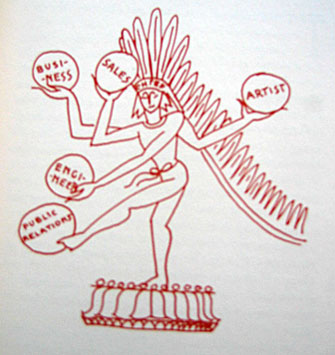

On mobile, users prioritise simplicity and speed over flexibility and broad functionality. Apps have a single use-case or purpose, as opposed to web products, or pre-mobile software in general, which cater for maximal different use-cases and functionality.

This is all a further acknowledgement that the paradigms that drove software and user behaviour in the pre-mobile world don’t fit completely to mobile, and the platforms are still evolving and changing.

Benedict Evans has posited that we really don’t know what it even will mean in 5 years to say “I installed an app on my smartphone”. So very little is settled – which means big opportunities – and also big risk – for mobile players.

“From the book

“From the book