It’s a question that every tech startup or product has to ask itself: when the budget is limited (and it nearly always is), where do you spend your cash? On improving the product, or on marketing and advertising campaigns? To me, the answer is clear: every dollar spent on advertising is a dollar not spent improving the product. Can you afford that? Can your product afford that?

But what do you do if you don’t have money to spend on marketing?

Twenty years ago to reach a million people with a message you needed to run a TV ad during a prime-time TV show or book a page in the national newspaper. If you wanted to sell your product to 1 million people, you just needed to insert enough advertising cash. Insert x dollars: ship y units.

Today, thousands of blogs, YouTube videos or Tweets reach millions of people every day. And it’s free.

Every individual has a reach now through the internet far greater than ever before. We can communicate messages immediately with our friends, who we trust, as well as broader social networks, easily, and it’s practically free. Everyone in your product team – from the product manager to the last software tester – is a potential marketer, reaching out to their social networks with a trusted and genuine message about your product.

In the world of web products, the products themselves have far greater reach and avenues to be found in the web than any physical product on a shop shelf could ever hope for. You can leverage Facebook and other social networks to promote and talk about your product, as well as create conversations with and between users. You can use Facebook as a platform to publish individual activity or status from the product, which has the dual benefit of strengthening the user’s social feed as well as promoting the product to every one of that user’s trusted network of friends. Pay a little bit of attention to SEO (Search Engine Optimisation) and you can target and optimise incoming traffic from search engines.

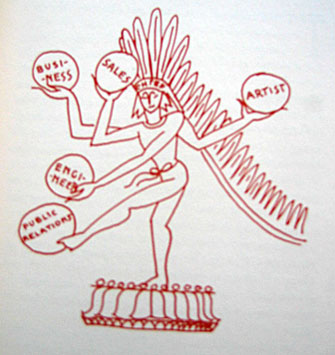

Guerrilla marketing campaigns like this one might be limited to a fairly local reach, but they are cheap (and fun!) to execute. Getting the whole team involved in local guerrilla campaigns can also be great for morale. The best performing and self-organising teams look at the whole end-to-end of their product – and marketing is no exception.

Today everyone’s a marketer. Getting the word out, finding more users, getting more traffic: these are no longer only the marketing team’s responsibility.

“From the book

“From the book