My last post about User Stories and putting the value for the user first in any product decision generated some great discussion on Twitter. As with anything there are some varying views on the topic, and as one example I was pointed to Liz Keogh’s post on user stories.

Liz argues that User Stories should be better named “Stakeholder stories”, as the things you build are addressing the needs of varying groups of stakeholders, only some of which are the end user.

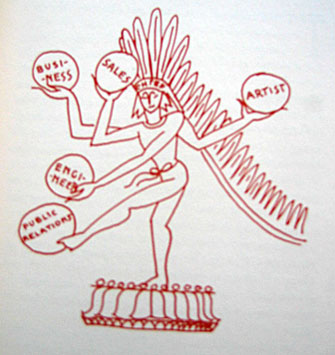

In the creation of any product there are of course many stakeholders who need to be satisfied: the CEO, shareholders, investors, marketing people, the legal department, and so on. In the design of the business, of course the internal stakeholders have the most important requirements. What sort of market are we going into? What segment will we serve? What problem or user need do we attempt to address with this product?

But when you start designing the product that the user will have in their hands, then the user needs to be at the heart of that design solution. Here, the user needs have to come first.

But what about all the stuff that you have to build into products that users don’t want, or even hate? Stuff like CAPTCHAs during registration processes, or advertisements? If the user’s needs come first, why does this stuff exist? To answer this, let’s take a step back and look at where user stories come from.

User Stories are not immaculate conceptions: they don’t just appear out of the blue, but they are thoughtfully created to address needs of the product and the business. On other words, they are derived out of the product vision and the surrounding business model.

If your business model involves monetisation through advertising, then you have a problem to solve: “how can I enable advertising in my product?” It’s clear that the user is not at the heart of the decision to enable advertising, but business models are complex and have to satisfy many stakeholders and solve many problems. At the business strategy level, the end-user is only one of multiple players, and the user doesn’t always come first.

So you have this problem: you have to enable advertising. How do you solve it? Do you slap a full-screen takeover banner for some random personal hygiene product on your start screen? Probably not. Do you enable Google AdWords to show advertisements relevant to the content in a meaningful way? Getting warmer. Do you study the user’s interaction on the page to determine where the advertisements should be placed and how they should be visually displayed to ensure that users understand what is a sponsored link and what is your own content, to avoid frustration and confusion from the end user and maximise the meaning and value they get when they interact with the advertising? Better still.

What is at the heart of each of these decisions? The user. This is where the user comes first – in the design of the solution to the problem. In the User Story.

User-centric design doesn’t absolve you (regrettably) of the need to be aware of the business context or the constraints of your business or industry: it merely proposes that the user is at the heart of how you solve your product problems and how you work with the constraints. Keeping the user at the centre of your user stories by insisting they start with “As a User…” helps you stay focussed on the people who will be interacting with the stuff you’re building.

“From the book

“From the book